Former Microsoft exec is still riding waves of the future

Monday, November 13, 2000

By Kristin Dizon - Seattle PI Reporter

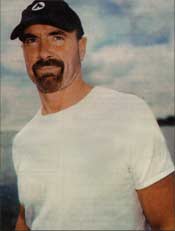

Somewhere, between the six flights, the myriad meetings and the gallon of coffee he drinks each day, an incidental thought infiltrated Rowland Hanson's mind one week in August.

It happened while the high-tech entrepreneur and sought-after consultant was meeting with a dot.com CEO at a Seattle restaurant.

"You know what I've checked out -- but I don't think they'll let you do -- is the ferries," mused Hanson, the former Microsoft marketing chief who coined the term "Windows" in 1983.

"I'll bet I can surf the wave behind a ferry."

"I'll bet I can surf the wave behind a ferry."

That casual conversation has become a mission.

And it's a metaphor for the way Hanson has combined his thirst for business with his passion for surfing. He eschews golf, the anointed sport of the business world, to take many of his associates and clients surfing near his Maui or Lake Sammamish homes.

Surfing the unbridled wave behind a ferry of at least 11,500 horsepower requires analysis and a strategy, much like what it takes in Hanson's specialty of creating an image for a company brand.

His reconnaissance so far has revealed that he'll need to drop in quickly after the ferry first shoves off, when the wave is biggest. The greatest danger will be to not get sucked under the stern of the boat.

Officials for the state ferry system and the U.S. Coast Guard, which sets and enforces navigational rules, say ferry-wake surfing, while not explicitly illegal, is strongly discouraged.

If Hanson does it, he won't be riding the mythical perfect wave that some surfers search for all their lives, but it definitely will be different.

Though the challenge of the ferry still looms, Hanson already has mastered smaller boat-created waves, carving up the wake from the back of his powerboat.

Call it surfing, Lake Sammamish style.

Surfer, but no slacker

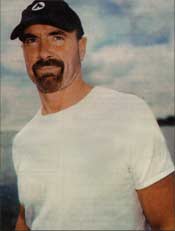

Hanson, 48, is a true believer, a devotee to the high temple of surfing. If there were a surf God, Hanson would burn incense and make offerings in supplication for great waves and great rides.

But unlike most surfers, Hanson has never been a wave-chasing disciple of surfer slackerhood. He hasn't camped on someone's lawn or lived in a van for months at a time.

Among surfers, Hanson is a rarity -- a wave rider who happens to be a successful businessman. Or is it the other way around?

While on Maui, where he spends almost half the year, Hanson surfs with men half his age. Most are bellhops, waiters or other workers low on the totem pole of Hawaii's tourism industry.

And they have no idea that this tan, muscular man, the one with the copious freckles, the one they fondly call "Pops" -- which Hanson detests -- is an early veteran of Microsoft who is financially secure, with a capital S.

Hanson still holds most of his original stock in the company, but he was successful before Microsoft, working for General Mills and Carnation until he was lured to an unknown software firm from the cosmetics company Neutrogena.

In 1983, a head-hunting firm contacted Hanson to tell him about a little company near Seattle.

"I said, first of all, where is Bellevue, Washington?" he recalls. "As far as I'm concerned, it's outer Siberia. And what is a Microsoft? I didn't even own a computer."

But Hanson was impressed with the vision that Bill Gates laid out during their Sunday lunch. There was only one thing he didn't get -- why did Gates want him?

Gates responded with a question: What is the difference between a moisturizer that costs $1 an ounce and one that costs $100 an ounce?

Hanson replied that there was little difference, technically. It was all in the subtle art of creating an image and desire for a particular brand.

That's why I want you, Gates said.

"The guy made so much sense, and still I didn't want to come," said Hanson, who had hoped to start his own business. "It's a testament to Bill Gates' persuasiveness. I literally said no for three months."

According to the book, "Barbarians Led by Bill Gates," when most of the software developers wanted to call the company's new operating system Interface Manager, Hanson, the vice president for corporate communications, championed the name Windows.

Hanson quickly immersed himself in his new techworld, but adapting to Rainville wasn't easy for the self-described beach boy. "I was miserable," he said.

So he coped by buying a home on Maui. (Yeah, he knows, rough life.)

"Going to Maui and being able to surf is very important to me," he said. "It's my soul."

But what to do about the times here, in oceanless Bellevue? If you're a problem solver like Hanson, you look at the Mastercraft powerboat at your dock and you naturally think,"Surf's up!"

Lake surfing

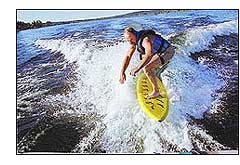

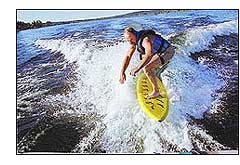

On a sunny fall day, Hanson shows a reporter his lake-surfing method.

It starts when he piles nine people into the back of his boat, which will kick up a 2.5- to 3-foot wave in its wake.

He jumps in the water, holding his yellow board perpendicular to the boat. While he holds on to a 10-foot-long purple tow rope, Hanson's body reclines in the water while his feet rest on the board.

When the boat starts moving, Hanson slams his ankles down hard onto the board and stands up. Then he pivots his body to face the boat.

For awhile, he uses the rope to catch some air, slice up and down the tube of the wave, even do a 360.

Then he pulls within a few inches of the boat and lets go of the rope.

Voila! Boat surfing, and so close we can touch him. Five full minutes of surfing -- compared to, say, a natural wave ride of maybe 30 seconds -- enough to make your legs turn to Jell-O if you're not in shape.

When he feels like it, Hanson simply hops onto the boat, reaches down and grabs his still bobbing surfboard.

Sure, it's not Hawaii or even Westport, but it's convenient and better than nothing.

"If it's in your blood, it's in your blood. You find a way to surf," Hanson says.

The surfing life

The thrill of becoming one with the waves started as a form of minimalist baby-sitting.

Hanson's two older brothers, both surfers, constantly dragged him to the beach.

"They said, 'If we're going to have to watch you, here's a board. You make a decision -- you can sit on the beach all day or you can surf.'"

The brothers didn't give him any tips.

"They said, 'Don't drown, or Mom and Dad will be mad'."

He was 6. He could surf before he learned to ride a bike.

At 8, Hanson became a junior lifeguard and got some true surfing lessons.

Then he turned the tables on his baby sitters. "I went to the other extreme. My brothers would want to leave and I refused to get out of the water. They'd have to paddle out and get me."

In high school, Hanson was the thick-necked, beefy captain of the football team. Named to several all-star teams, he hoped to turn pro until he fractured his neck. His quarterback was George Allen, former Republican governor of Virginia elected last week to a U.S. Senate seat from that state.

In high school, Hanson was the thick-necked, beefy captain of the football team. Named to several all-star teams, he hoped to turn pro until he fractured his neck. His quarterback was George Allen, former Republican governor of Virginia elected last week to a U.S. Senate seat from that state.

Surfing as a theme runs through Hanson's life. He met his wife, Mary, with surfboard subterfuge. "Haven't I seen you before?" asked the high school senior of the freshman as they waited for waves to ride. He'd never seen her in his life, but the line worked.

The couple has been married 29 years. In the early days, with baby Vanessa in tow, they'd driveto Mexico for the weekend to surf. During the week, Hanson was a student at Loyola University and worked full-time as a security guard at an elementary school to support his family.

After graduation, he went straight to the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania for his master's degree.

"All of my friends, who were surfers, looked at me like, why would you possibly go to Philly? There's no surf," he said.

Now, oldest daughter Vanessa Tormey is married to a surfer from Hawaii and middle daughter Liberty Hanson's boyfriend is a surfer. Hanson jokingly says he needs to find a surfer for his youngest daughter, Corey.

In demand

Hanson's business acumen and extensive connections are such that start-ups woo him for advice or to sit on their boards.

"He's definitely a hot commodity," said Glenn Ballman, founder and CEO of Onvia.com, which has Hanson on its advisory board. "The reason people want him is that he's seen so much and been through many experiences. He's got a proven track record and he's also a great deal of fun to work with."

In earnest, but with a hint of a laugh in his voice, Ballman said, "I hope he's not too well known because I don't want his time taken up by others. No offense, but I hope your article's buried on the last page."

So why does a man keep working when he can afford to retire and just play?

Why does Hanson, who has more than a million frequent-flier miles on United Airlines, spend his time crisscrossing the country on red-eyes, meeting people in airports for a few hours before hopping another jet for another destination for another meeting?

Because the guy who was a computer novice when he landed at Microsoft has embraced the high-tech way.

He left Microsoft after three years to start his own consulting business. Now he works mostly with start-ups seeking a foothold in the market and he thinks there's money to be made, in spite of recent stock plunges and dot-com casualties.

"It's always something truly new and it's having a major impact on how businesses conduct business and how people live their lives," Hanson says. "I couldn't sit on my lanai for two weeks at a time and surf on Maui if I didn't have e-mail."

Not only does Hanson work 70 to 80 hours a week. He prefers thorny problems and challenges.

"I love making things happen," he says. "Something that's very easy is not interesting to me. When things go awry, I'm much more motivated to stay up all night and fix them. If things are going well, I'm bored."

He sleeps four to five hours a night to "get the most out of my life at all times."

A typical day for Hanson starts at 4 a.m. He drinks a pot of coffee by 7 a.m. and starts a second one brewing. When he's in Hawaii, he eyes the surf in the early morning as he fires off e-mail, then heads to the beach when the waves look good.

He's not a monster-wave or trick rider, but he's aggressive about taking on tough 10- to 15-foot waves, which can pummel and pin you under until your lungs burn for lack of air.

He continues to use a short board while many men his age have switched to the gentler long board. And he likes the fact that every single wave is different.

Like most surfers, Hanson says the feeling, the devotion, the purity of his sport can't really be communicated to outsiders.

"It's one of the most peaceful, tranquil things. It's almost intoxicating," he says. "Surfing really is a cult. When you run into another surfer, the situation doesn't matter. You have a common bond."

Shark phobia

It's apropos that the man called a "water rat" by one of his daughters was born under the sign of Pisces.

A bit unexpected is Hanson's fear of sharks, which obviously hasn't stopped him from mingling in their environment.

While he's never been bitten, he did have a run-in with one about 10 years ago. Hanson was surfing at one of his favorite Maui beaches at dusk. As the last surfer in the water, waiting for a wave to ride into shore, he felt a bump on his board.

"The first thing that goes through my mind is that I hit a rock," he says, pausing to build suspense. "Then, I realize" -- pause again -- "there's no rocks out here."

Deep-throated, belly-firming chuckles erupt -- a winsome reaction now from a man who thought at the time he might become human sushi for Jaws.

"And you're not supposed to splash. But what do I do? I take off for shore. It's one thing to tell somebody not to splash. It's another thing with a shark over there looking at you. Oh yeah, like I'm gonna be cool."

"I have never paddled so fast in my life," Hanson says earnestly. "As I hit the beach, I kept running up the trail to my car."

Regaling a group of friends and business clients with the tale over beers on his Lake Sammamish lakeside lawn, Hanson enacted one of the recommended techniques for dealing with a shark attack: you're supposed to fight back by punching the shark in the snout.

Laughing, he says, "I'm just gonna fake to the left."

Then he takes over the role of the shark: "Oh yeah, I've seen that hook before -- from the last guy I ate."

Intense but laid back

Hanson does have something in common with the object of his phobia: He sinks his teeth into his pursuits.

Take tennis: Once he decided to play nearly a decade ago, he practiced nearly every day.

"Rowland could hit the ball to the moon if he wanted," said Darrell Abang, a tennis pro at Bellevue's Pro Sports Club. "Once he focuses on something, he'll go until he can get as good as he'll get."

"Rowland could hit the ball to the moon if he wanted," said Darrell Abang, a tennis pro at Bellevue's Pro Sports Club. "Once he focuses on something, he'll go until he can get as good as he'll get."

Oxymoronic as it may seem, Hanson blends his trademark intensity and total focus with a down-to-earth attitude.

"Given how successful he's been, my dad's not materialistic in his thinking," said oldest daughter Vanessa. Hanson's ways have rubbed off on her in more ways than one: Tormey is the marketing director for Inter@ctive Week, an online roundup of the wired world.

"I think the beach lifestyle has followed him his whole life. Any person he meets he treats with the same level of respect," she says.

Hanson has two stepbrothers who embody the full-time surfing lifestyle in Hawaii. One lives in his car and drives around looking for waves. The other lives in a shack without electricity or water and shaves surfboards for a living when not surfing.

"They are very happy. They have few material things, but they have a lifestyle that they wouldn't trade for anything," Hanson says. "Most people don't understand that. But I don't think it's strange at all."

While Hanson isn't planning to live similarly, he knows one thing: "I'll keep surfing till I die."

And asked if he'll really surf the ferry wave, or even if it's possible, Hanson replies, "Oh, I'm going to do it. There's no question."

"I'll bet I can surf the wave behind a ferry."

"I'll bet I can surf the wave behind a ferry."

In high school, Hanson was the thick-necked, beefy captain of the football team. Named to several all-star teams, he hoped to turn pro until he fractured his neck. His quarterback was George Allen, former Republican governor of Virginia elected last week to a U.S. Senate seat from that state.

In high school, Hanson was the thick-necked, beefy captain of the football team. Named to several all-star teams, he hoped to turn pro until he fractured his neck. His quarterback was George Allen, former Republican governor of Virginia elected last week to a U.S. Senate seat from that state.

"Rowland could hit the ball to the moon if he wanted," said Darrell Abang, a tennis pro at Bellevue's Pro Sports Club. "Once he focuses on something, he'll go until he can get as good as he'll get."

"Rowland could hit the ball to the moon if he wanted," said Darrell Abang, a tennis pro at Bellevue's Pro Sports Club. "Once he focuses on something, he'll go until he can get as good as he'll get."